The laccolith shoulders this inelegant sky, nothing to write home about, as if this weren’t home now but that other place, the one I’m from, a town that’s rotting building by building, foundation by foundation, the fences, the red brick, the sweetgums and their dejected seeds. But mostly the psychiatric hospital, which the state left to vandals years ago.

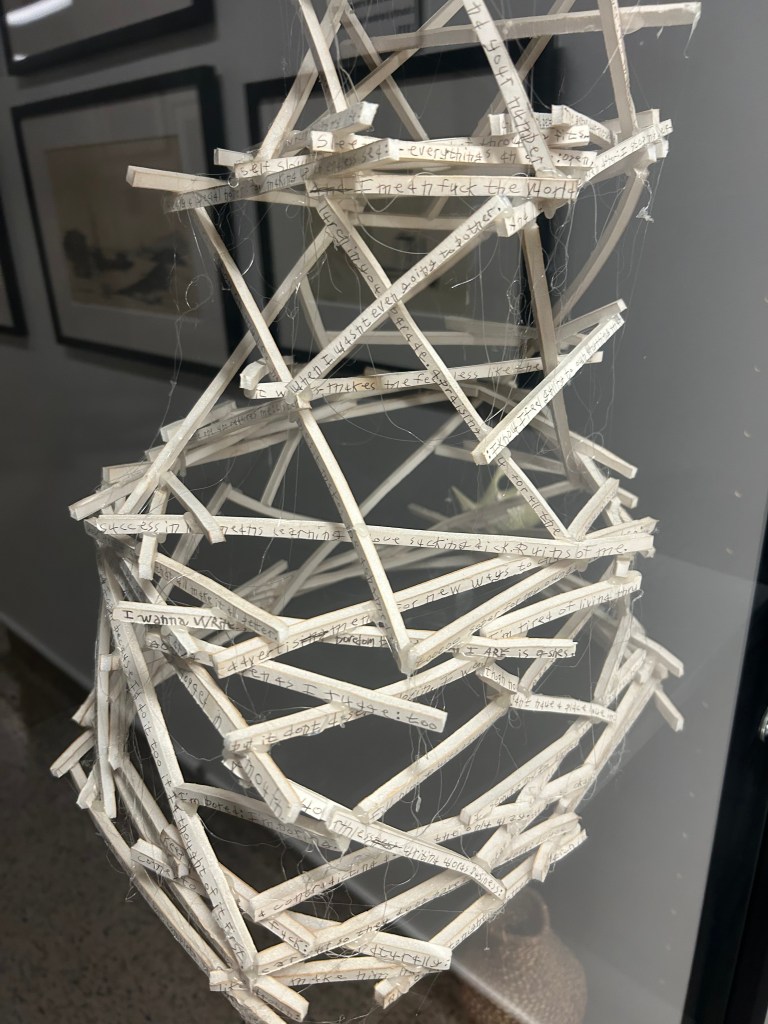

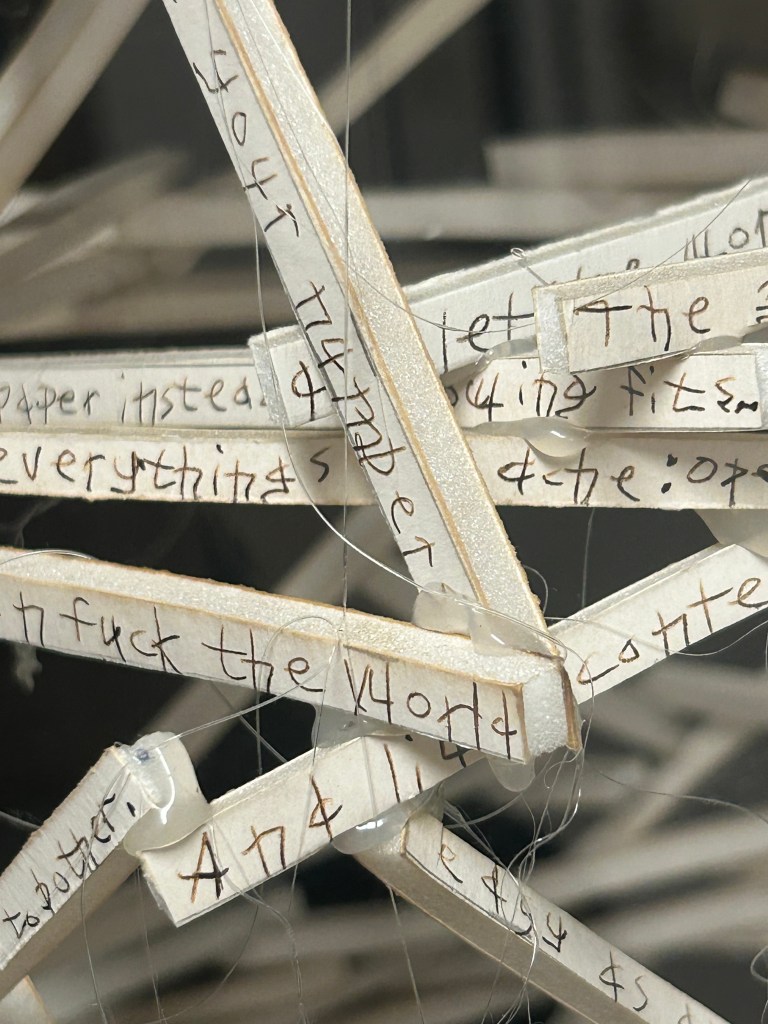

Where I live now is less town than scrub, less scrub than sand, less sand than canyon. Plenty of room for a word to get lost, to go out on the air and never reach a listener but also never boomerang back to the speaker who stands, silent, beyond language, at least for a spell, isolated from everyone, including themselves.

That’s when the laccolith comes in handy, a kind of giant anchor for thought, for yearning. Headless under dark clouds, the color of night before night falls. A heavy future, a heavy past, a sense of always about it that makes humans seem like baubles, a bracelet of seals surrounding a whale in a faraway watery world before one slips into its mouth unnoticed.

What rises here rises in the distance, with its monzenite and spruce, big-eared bats and fir, bitter cherry, dollarjoint cactus, pygmy rabbits, sandweed, spleenwort. We’ve never been liberated from names or naming. In my ignorant past, I didn’t learn what to call things or what to call myself. Cardinal was red bird. Finch was sparrow. Father was father. I was daughter.

I read that if you think enough about a relative, your genes flip on and off to become more like theirs. Ten minutes a day for thirty days is all it takes. In case that’s true, who should I think of? I’ll take my chances with my mother, the way the white-tailed antelope ground squirrels take their chances with the feral cat when the neighbor’s trees are heavy with apricots in late summer. At least her genes helped me survive him.

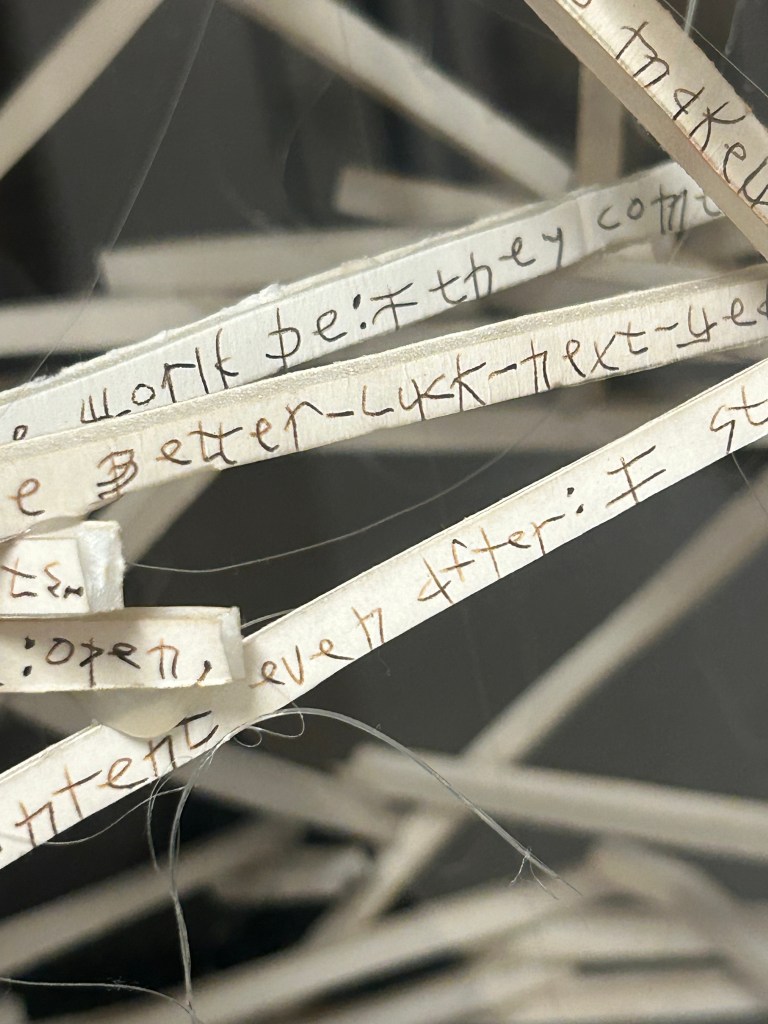

Pistachios escaped cultivation in nearby mining towns and made their way up into the mountains. Birds, the first landscape architects, move them around the foothills, where they grow like bonsai. Humans spread from place to place, trying to find and lose ourselves. We look for footholds. We lock in. Even if we only grow a little, it’s something. A small life is better than none at all.

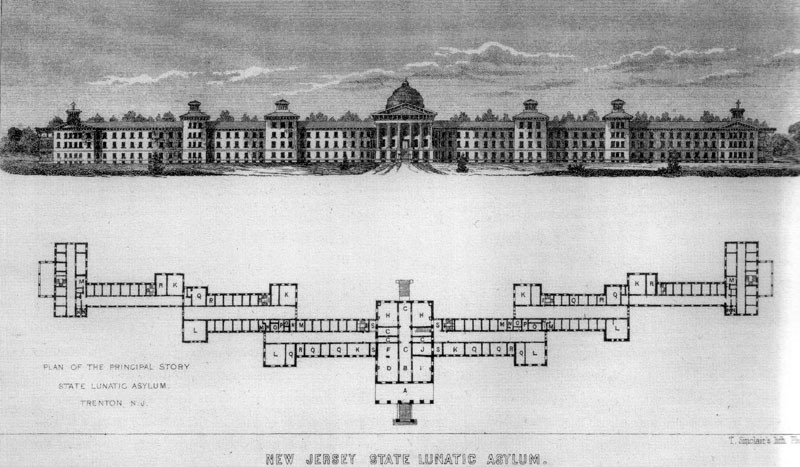

Horses and cows come and go here, the way they do where I’m from. My mother came and went, into and out of the hospital as a nurse and sometimes as a patient. Those buildings feel like her body rotting, returning to earth with no dignity. Her broken windows. The word PSYCHO spray-painted on her side. Her interior waterlogged and full of God knows what in the one-time hospital chapel that hasn’t shivered with song in decades.

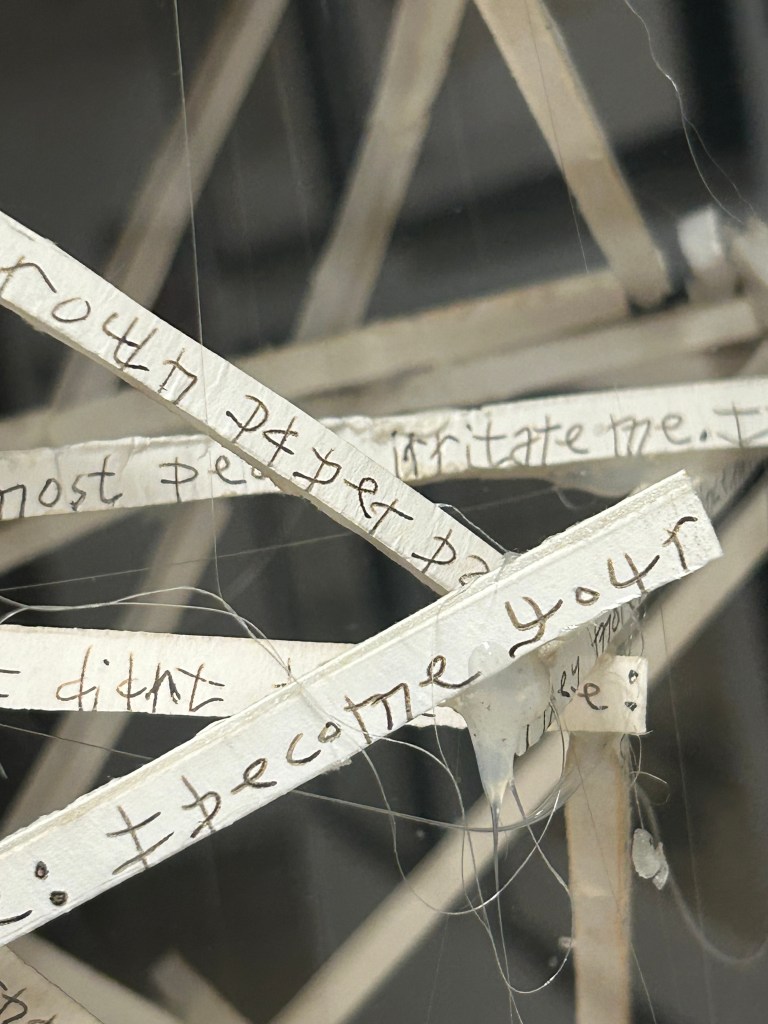

Inger Christensen says there is war all the time. There is war. There is war. War in the cells. War in the genes. War in the heart. War in the mind. War in the family. War in the mother. War in the father. But there is also deerweed and spikemoss, manzanita and mat muhly. There is histone modification and methylation, expression and heritability. There is asbestos and lead, observation hatches and safety glass.

There is what happened and what passes for what happened, in memory, in polite company, in our palm lines, in our bloodlines. There is war all the time, even under new paint and old dirt.