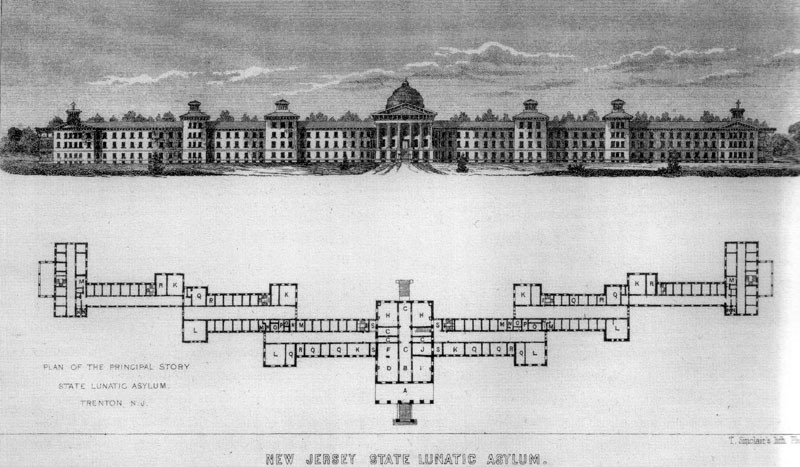

Mental illness has an architecture. That’s part of the story of asylums and treatment in this country. Central State Griffin Memorial, the hospital in my hometown, wasn’t laid out like this, but it had that same grand feel juxtaposed against the lives of those who inhabited the buildings.

Throughout its history, which spans more than a century, Central State’s story has been one of hope, ignorance, dehumanization, and harm: the same story from the asylum era to era of deinstitutionalization to today. I can barely tell any of it but have to before that history is lost. My mother worked there as a nurse and was treated there as a patient. Her relationship with Central State spanned more than three decades. That architecture was in her body, her bones part of the structure of those buildings and that land. Now, we need to make sure these places don’t come back with a new story: one of coercion, exploitation, profit, and greed.

—

Source: PBS Utah video about The Kirkbride Asylum, which was the template for many other asylums across the country.