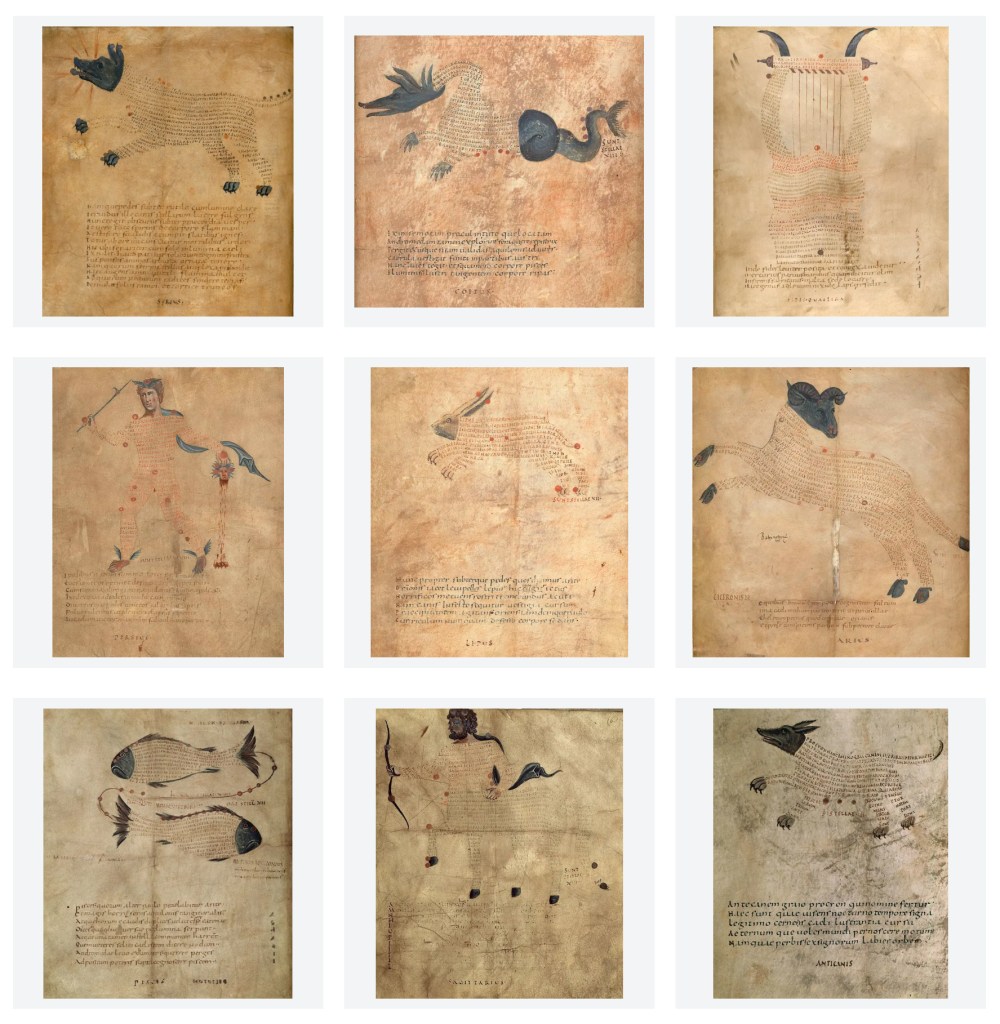

Folks were really reaching to find animals in the stars. I’m glad they did, otherwise we wouldn’t have these calligrams.

Source: Public Domain Review.

Folks were really reaching to find animals in the stars. I’m glad they did, otherwise we wouldn’t have these calligrams.

Source: Public Domain Review.

Here’s what could get you lobotomized at the age of 12 in 1960 here in the United States: not reacting to love or punishment, objecting to going to bed but sleeping well, daydreaming and not discussing the content of the daydreams, and turning the lights on in a room when it’s sunny outside.

These are the “symptoms” that led to Howard Dully being institutionalized from the age of four and undergoing a trans-orbital lobotomy in which an orbitoclast was inserted into his brain through each of his eye sockets.

Please don’t make jokes about lobotomies or about mental-health issues and treatments in general. And please realize that we’re headed backwards in this country where mental healthcare is concerned. Lobotomies may not be in our future, but barbaric treatments and human-rights abuses are. I pray I won’t live long enough to see them or to be on the receiving end of them.

For me, the pronoun they works on many levels. One complaint about using they in the singular is that it’s grammatically incorrect. But is it? The mind is plural and decentralized. We may be one, but “I” may not even be a thing other than an understanding between us, a kind of “you there, me here” shorthand, a fiction that appears to simplify living. They is a better pronoun for me than he or she any day. It does more than help me escape the waist trainer of gender essentialism. It helps me remember that my mind is not one and never was and never will be.

Just as I was falling asleep again after the recurring nightmare about the house with thirty basements that are actually a portal to hell, the fire alarms went off in our house, making it, too, a portal to hell, an existential one that can only be reached by way of six interconnected wireless fire alarms blaring and yelling FI-YUR FI-YUR FI-YUR all at once.

This is the third time this has happened in less than a year with these fancy alarms the life partner installed, the ones that should last ten years with no issues. Maybe time’s moving faster than I think. Maybe years are decades and decades are eternities. Maybe I’ve been here forever and so have you.

The alarms are terrifying our dog, wrecking our sleep, and allowing my body to rehearse going into flight mode, which isn’t what it needs to be doing. My intestines got so upset, I think they consumed themselves and left a ball of iron in their place. I guess I’ll have to learn to live on air and remember to avoid MRI machines.

I’d rather die in a house fire than ever hear another fire alarm go off. I said what I said.

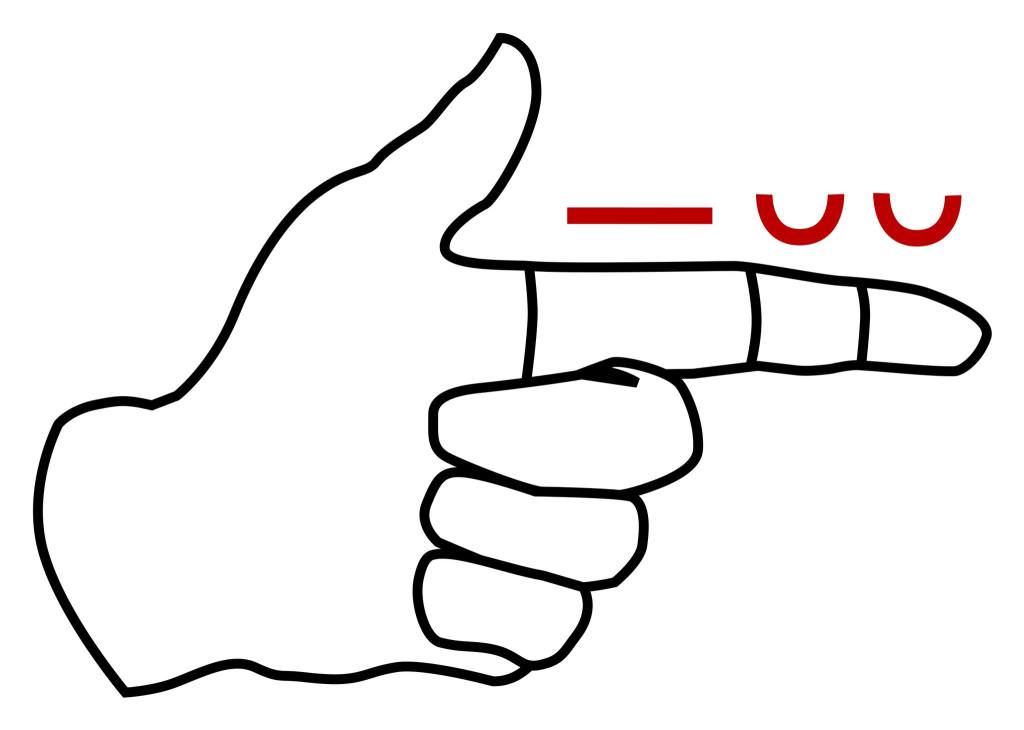

Made by modifying a Creative Commons image from Wikipedia that uses a hand to illustrate a dactyl. Inspired by a conversation with Elizabeth Macduffie. I want to make this into a T-shirt.

This pond is old as / me. That’s how bad-off it is. / Frog-visits, I doze. — Bill Knott

Source: Bill Knott Archive.

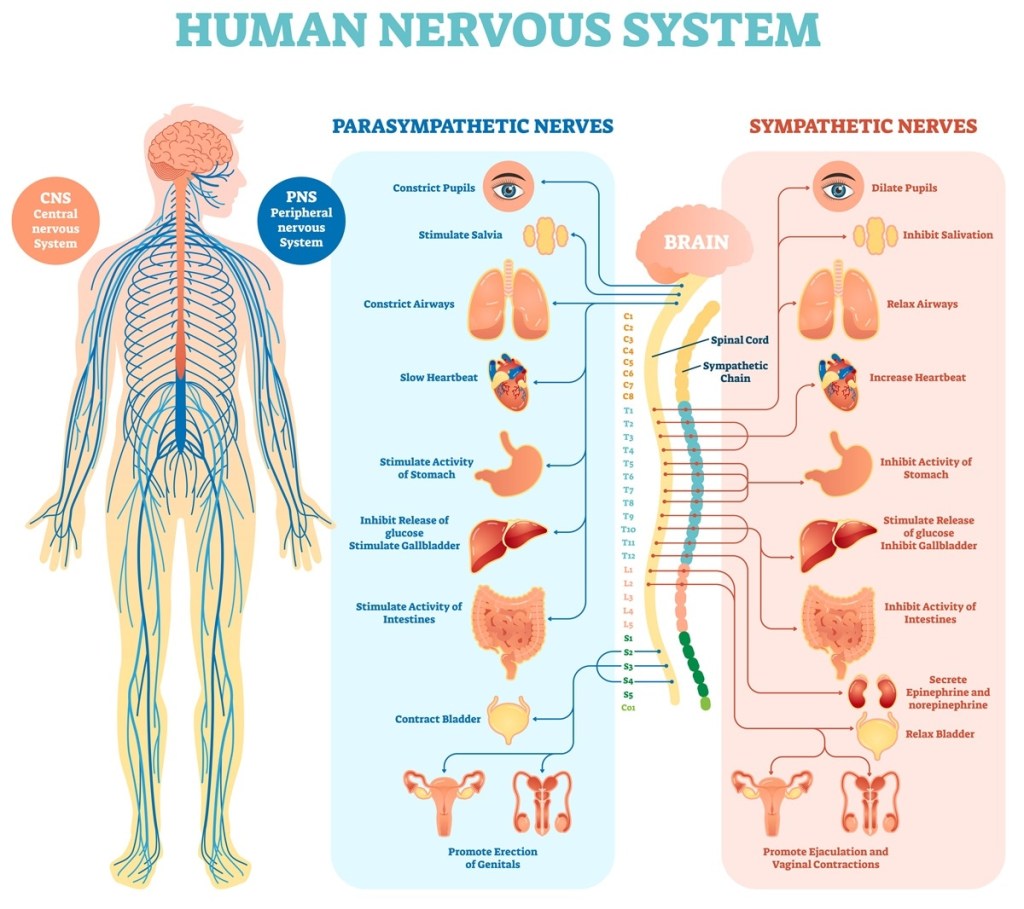

Neuro- is a combining form that means nerve, nerves, and nervous system. It does not mean brain, though the nervous system includes the brain. So when I talk about neurodiversity, I am not reducing folks and their experiences, identities, or labels to their brains, and I am not situated inside any kind of bioessentialism or biomedical framework. We are biological organisms. Everything that happens to us is biological. Our biological experiences are largely informed by our nervous systems. Our nervous systems are—both acutely and chronically, and both idiopathically and collectively—affected by everything around us, including our experiences, our abuses and traumas, the ways in which we are marginalized and oppressed, and more. Saying something is neuro-, including using terms like neurodiverse within the framework of neurodiversity, is not saying this, that, or the other thing starts and ends in the body. It is not the equivalent of denying or discounting the larger systems, functional and otherwise, in which we as biological beings exist or the forces those systems exert on our lives.

Image: A graphic depicting the human nervous system, including the parasympathetic nerves and the sympathetic nerves. The functions of the former include constricting pupils, stimulating saliva, constricting airways, slowing heart rate, stimulating stomach activity, inhibiting the release of glucose, stimulating the gallbladder, stimulating the intestines, contracting the bladder, and promoting the erection of genitals. The functions of the latter include dilating pupils, inhibiting salivation, relaxing airways, increasing heart rate, inhibiting stomach activity, stimulating the release of glucose, inhibiting the gallbladder, secreting epinephrine and norepinephrine, relaxing the bladder, and promoting ejaculation and vaginal contractions.

Image source: News Medical.

In September 1994, [David] Bowie and Brian Eno—who had reunited to develop new music—accepted an invitation from the Austrian artist André Heller to visit the Maria Gugging psychiatric clinic. The site’s Haus der Künstler, established in 1981 as a communal home and studio, is known internationally as a centre for Art Brut—or Outsider Art—produced by residents, many living with schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders.

The acclaimed Austrian photographer Christine de Grancy documented the visit, capturing Bowie engaging with these so-called outsider artists—a term often criticised for framing artists through illness or marginality rather than authorship. For the first time, these intimate portraits will be shown in Australia, when A Day with David opens at Joondalup festival in Western Australia in March, in collaboration with Santa Monica Art Museum.

And, of note: Gugging itself carries a darker weight. Founded in the 19th century, the clinic was later absorbed into the Nazi’s Aktion T4 program, which targeted those with mental and physical disabilities, and resulted in the mass murder of an estimated 250,000 people. At Gugging alone, hundreds of patients were murdered or sent to extermination facilities.

Source: The Guardian.

Poetry is my weapon. Baby, you don’t wanna mess with these dactyls.

Image: an outline of a left hand with the thumb pointing up, the bottom three fingers folded back, and the index finger pointing out. A long red line (representing a stressed syllable) is above the finger’s bottom bone (proximal phalanx), as well as two red curved lines (representing unstressed syllables) above the middle and upper bones (middle and distal phalanges). Image fromWikipedia and used in accordance with its Creative Commons Universal license.

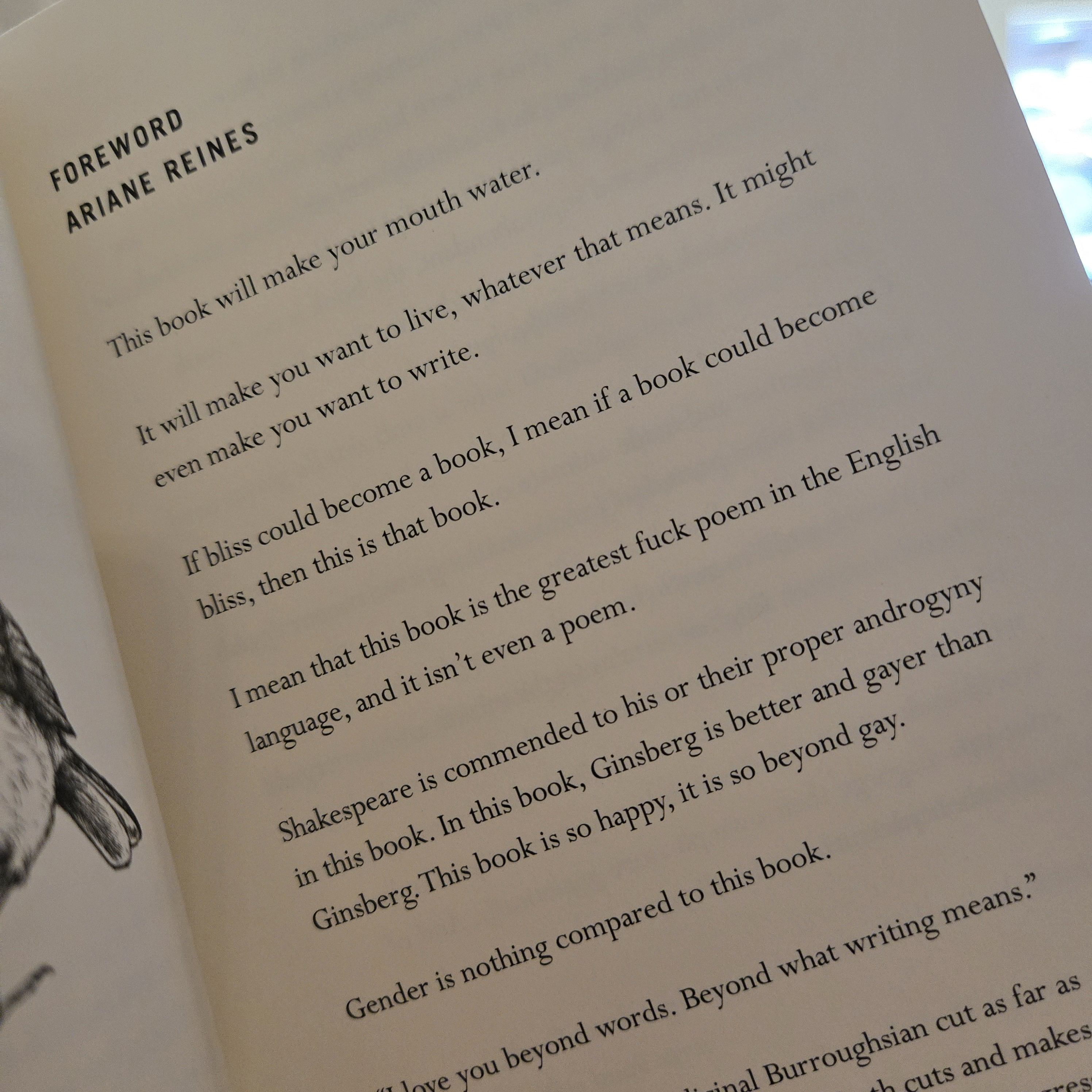

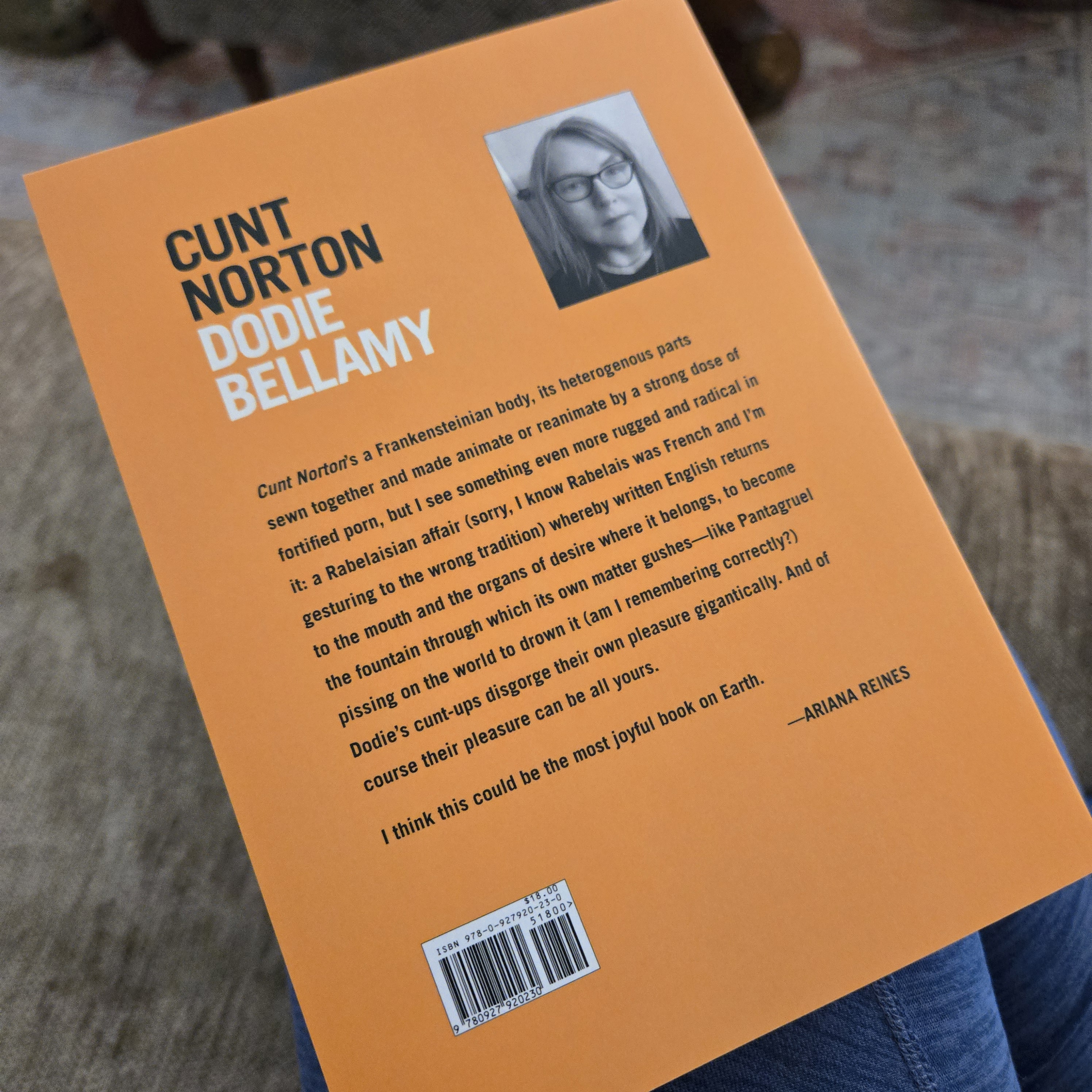

Why am I scarfing down a whole thing of chocolate hummus all at once? Because I’m reading Cunt Norton, by Dodie Bellamy. Here’s an excerpt from the introduction by Ariane Reines:

This book will make your mouth water.

It will make you want to live, whatever that means. It might even make you want to write.

If bliss could become a book, I mean if a book could become bliss, then this is that book.

I mean that this book is the greatest fuck poem in the English language, and it isn’t even a poem.

Shakespeare is commended to his or their proper androgyny in this book. In this book, Ginsberg is better and gayer than Ginsberg. This book is so happy, it is so beyond gay.

Gender is nothing compared to this book.

If you hear me screaming yes yes yes with my volume maxed out, trust me: I’m just reading this book.

(Personally, I think it is a poem.)